The financial media is drawn to catchphrases –acronyms and buzzwords that can be sold as the new thing. ‘FAANG’ (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) is the latest of these. But does this constitute an investment strategy?

For journalists, commentators and marketers, acronyms like FAANG are useful. They fit easily into headlines, and they appeal to a feeling among some investors that their portfolios should match the ‘zeitgeist’ or spirit of the age.

But as we’ll see, investment trends tend to come and go. This is not to downplay the transformative nature of new technologies and the possibilities they present. But as an investor, it is wise to recall that all those hopes and expectations are already built into prices.

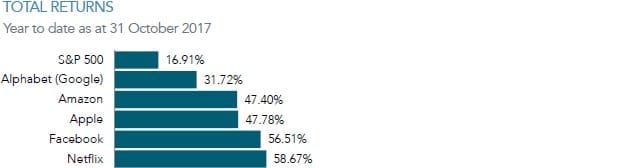

The FAANG acronym has become particularly popular in 2017 as returns from the five members of the unofficial club have far outpaced the wider market. The table below refers to Alphabet, which is the listed company that Google is a part of.

Such is the public interest in the tech giants that the parent company of the New York Stock Exchange recently launched a ‘FANG’ futures index that includes the quarterly futures contracts of the FAANG members apart from Apple (hence only one ‘A’), plus another five actively traded technology growth stocks.

So, does this mean, as some media gurus suggest, that you should reweight your portfolio around these tech names? After all, these companies have fundamentally reshaped traditional sectors like newspapers, television, advertising, music and retailing.

For investors, there are a few ways of answering that question, none of which involve denying the significant influence Facebook, Amazon, Apple Netflix, Google and other technology names are having on our lives.

Firstly, market leadership is constantly changing based on a myriad of influences, including shifts in the structure of the global economy, commodities, technology, demographics, consumer tastes and supply factors. Trying to build an investment strategy by anticipating these forces is like trying to catch lightning in a bottle.

In the 1960s, the then often-quoted ‘Nifty Fifty’ of ‘solid, buy-and-hold blue-chips’ included such names as Xerox, Eastman Kodak, IBM and Polaroid, all of whom were disrupted in one way or another by newer, more nimble competitors in the following decades.

By the late 1990s, the media was full of stories about the ‘dot-coms’, companies that were building new businesses using the transformative power of the internet. A handful of those companies (Amazon for instance) fulfilled their promise. Many others (retailer Boo.com, prototype social network TheGlobe.com, and pet supplies firm Pets.com were just three examples) crashed and burned.

In the mid-2000s, the focus turned to companies with a large exposure to the so-called ‘BRIC’ economies. An acronym based on the fast-growing emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China.

One major investment bank even set up a BRIC fund, arguing that the superior growth outlook for emerging economies justified a bias to stocks exposed to these markets. By late 2015, however, the fund was closed after years of poor returns.

So, while individual sectors each can have their time in the sun, it is not clear that weighting your portfolio toward an industry currently in favour is a sustainable long-term strategy.

A second way of looking at this issue is that accepting it is difficult to pick winning sectors does not mean you should exclude these stocks in a diversified market-wide portfolio. You can still own them, but you do so by casting a much wider net.

The more concentrated the portfolio, the more you are exposed to idiosyncratic forces related to individual stocks or sectors. Being highly diversified means you can still benefit from the broad trends driving technology or whatever is leading the market at any one time, but you are doing so in a more prudent manner.

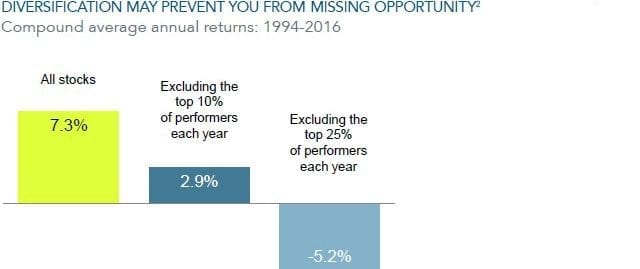

Put another way, by diversifying you are not only reducing the risk of placing too much of a bet on one sector, you are improving the odds of holding the best performers. Look at the chart below which shows what would have happened if you had excluded the top 10% and top 25% of market performers in a global portfolio from 1994-2016.

We’ve seen that even professional investors can find it tough to pick which sector will lead the market from year-to-year.

It’s true that technology companies like Amazon and Facebook have performed well recently. But it is worth recalling that current prices already contain future expectations about those companies. We don’t know what future prices will be because these will reflect information we haven’t received yet.

Because no-one has a reliable crystal ball, the best approach is to diversify. That way we increase the odds of being positioned in the next big winning sector but without chasing hot trends or latching on to cute-sounding acronyms. Talk to our financial advisers for more information about this article.

Stephen Lowry CFP, DFP, FAIM, is a representative of Alman Partners Pty Ltd, Australian Financial Services Licence No: 222107.

Performance data shown represents past performance or simulated performance. Past performance is no guarantee of future results and current performance may be higher or lower than the performance shown. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost.

Note: This material is provided for information only. No account has been taken of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular person or entity. Accordingly, to the extent that this material may constitute general financial product advice, investors should, before acting on the advice, consider the appropriateness of the advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This is not an offer or recommendation to buy or sell securities or other financial products, nor a solicitation for deposits or other business, whether directly or indirectly.