The lure of trying to time the market may tempt even long-term investors. But outguessing markets isn’t as straightforward as it sounds.

Over the course of a year, it’s not unusual for the stock market to be a topic of conversation at barbeques or other social gatherings. A neighbour or relative might ask about which investments are good at the moment. The lure of getting in at the right time or avoiding the next downturn may tempt even disciplined, long-term investors. The reality of successfully timing markets, however, isn’t as straightforward as it sounds.

Outguessing the Market Is Difficult

Attempting to buy individual stocks or make tactical asset allocation changes at exactly the “right” time presents investors with substantial challenges. First and foremost, markets are fiercely competitive and adept at processing information. During 2018, a daily average of $462.8 billion in equity trading took place around the world.1 The combined effect of all this buying and selling is that available information, from economic data to investor preferences and so on, is quickly incorporated into market prices. Trying to time the market based on an article from this morning’s newspaper or a segment from financial television? It’s likely that information is already reflected in prices by the time an investor can react to it.

Dimensional recently studied the performance of actively managed mutual funds and found that even professional investors have difficulty beating the market: over the last 20 years, 77% of equity funds and 92% of fixed-income funds failed to survive and outperform their benchmarks after costs.2

Further complicating matters, for investors to have a shot at successfully timing the market, they must make the call to buy or sell stocks correctly, not just once but twice. Professor Robert Merton, a Nobel laureate, said it well in a recent interview with Dimensional:

“Timing markets is the dream of everybody. Suppose I could verify that I’m a .700 hitter in calling market turns. That’s pretty good; you’d hire me right away. But to be a good market timer, you’ve got to do it twice. What if the chances of me getting it right were independent each time? They’re not. But if they were, that’s 0.7 times 0.7. That’s less than 50-50. So, market timing is horribly difficult to do.”

Time and The Market

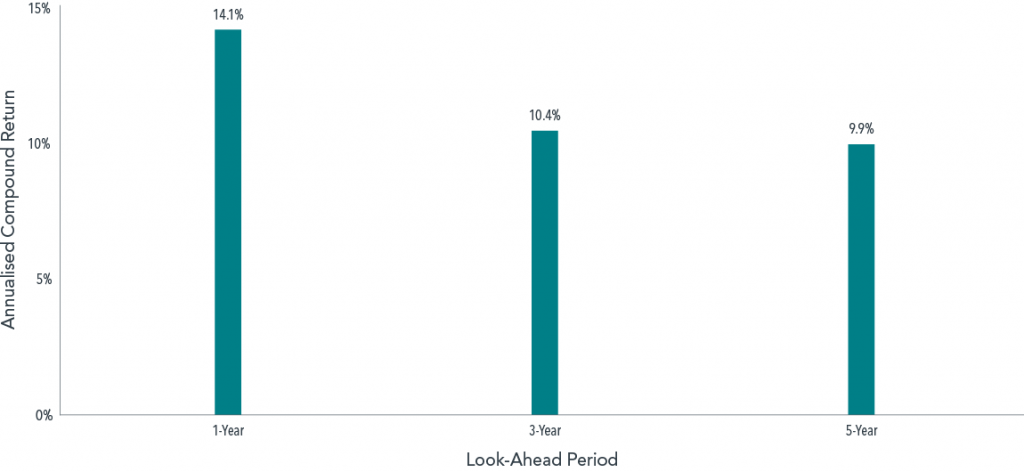

The S&P 500 Index has logged an incredible decade. Should this result impact investors’ allocations to equities? Exhibit 1 suggests that new market highs have not been a harbinger of negative returns to come. The S&P 500 went on to provide positive average annualised returns over one, three, and five years following new market highs.

Average Annualised Returns After New Market Highs

S&P 500, January 1926 – December 2018

Conclusion

Outguessing markets is more difficult than many investors might think. While favourable timing is theoretically possible, there isn’t much evidence that it can be done reliably, even by professional investors. The positive news is that investors don’t need to be able to time markets to have a good investment experience. Over time, capital markets have rewarded investors who have taken a long-term perspective and remained disciplined in the face of short-term noise. By focusing on the things they can control (like having an appropriate asset allocation, diversification, and managing expenses, turnover, and taxes) investors can better position themselves to make the most of what capital markets have to offer.

Article provided by our Guest Contributor Dimensional Fund Advisors

Alman Partners Pty Ltd, Australian Financial Services Licence No: 222107.

Note: This material is provided for information only. No account has been taken of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular person or entity. Accordingly, to the extent that this material may constitute general financial product advice, investors should, before acting on the advice, consider the appropriateness of the advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This is not an offer or recommendation to buy or sell securities or other financial products, nor a solicitation for deposits or other business, whether directly or indirectly.